TL;DR

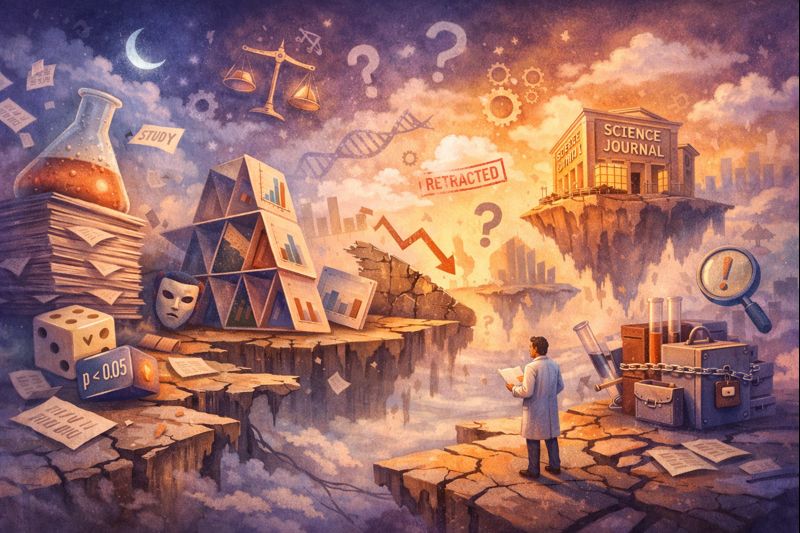

Reproducibility is the idea that scientific results should still hold when others repeat the same analysis or experiment. Over the past decade, many large replication efforts showed that a substantial fraction of published findings do not reproduce, especially in the life and social sciences. This is mostly not about fraud, but about incentives: journals reward novelty and “positive” results, replication is rarely published, methods and data are often incomplete, and statistics are pushed too hard under pressure to publish. The result is a literature that looks more certain than it really is. Open science emerged as a response, promoting transparency, pre-registration, data and code sharing, and new publishing models. Reproducibility matters because it is how science earns credibility: not by never being wrong, but by making it easier to find out when it is.

The Full Story

The Metaphor

Imagine a recipe that only works for the original chef. Others follow the same steps, use similar ingredients, and still get a different dish. At some point, you stop trusting the recipe: not because the chef was dishonest, but because something important was never written down, tested properly, or was tuned just enough to work exactly once.

That, in essence, is the reproducibility problem in science.

The Real Issue

Over the past decade, science has been forced to look at itself in the mirror. What it saw was uncomfortable: many published results could not be reproduced when other researchers tried to repeat them. This situation became widely known as the “reproducibility crisis” - or, more optimistically, what some now call a “credibility revolution.”

But what does reproducibility actually mean? Why does it matter beyond academic debates? And what is science doing about it?

Let’s explore this.

Reproducibility in Simple Terms

At its core, reproducibility asks a very basic question:

If someone else follows the same steps, do they get the same result?

In practice, this can mean different things depending on the field:

- Computational reproducibility: Can others rerun the same data and code and obtain the same numbers?

- Experimental replication: Can others redo the experiment - collect new data - and still observe the same effect?

- Conceptual replication:Does the underlying idea or hypothesis still hold when tested under different conditions, with different methods, or in different contexts?

A study can be perfectly reproducible in terms of code and methods, yet still fail to reproduce its original findings. This distinction turns out to be crucial.

Why the “Crisis” Emerged

Large, coordinated efforts to replicate published studies revealed an uncomfortable pattern:

- Many results, especially in psychology, medicine, and biology, failed to replicate.

- Replication studies themselves were rarely published.

- Journals strongly favoured novel, positive, statistically significant results.

- Methods and data were often poorly reported or unavailable.

One famous psychology project found that only around 40% of results replicated successfully. In some biomedical research, reproducibility rates were even lower - sometimes close to 10–20%.

This is not because most scientists are dishonest. Instead, it reflects how science has been incentivised.

Is Replication Always the Final Judge?

Philosophically, replication is more subtle than it first appears.

When a replication fails, two interpretations are possible:

- The original result was wrong.

- The replication was not done “properly”.

This creates what philosophers call the experimenters’ regress: to judge whether a replication is valid, you already need agreement about what counts as a correct experiment.

Despite this, replication still matters - not because any single attempt is decisive, but because patterns across many attempts gradually shift our confidence. Even repeated failures, none of them conclusive on their own, can collectively erode belief in a claim.

A Turning Point: The Rise of Meta-Science

Out of the crisis emerged a new field: meta-science, the scientific study of science itself.

Meta-scientists:

- Run large-scale replication projects

- Measure publication bias

- Study how incentives shape behaviour

- Test interventions to improve transparency

Their findings made one thing clear: science’s problems are structural, not moral.

The Open Science Response

In response, the open science movement has pushed for practical reforms:

- Pre-registration: stating hypotheses and analysis plans before seeing the data

- Data and code sharing

- Registered Reports, where studies are accepted before results are known

- Clearer reporting standards

- New incentives, such as open science badges

These changes aim to realign scientific practice with its core goal: getting closer to the truth, not just producing eye-catching results.

Values Matter More Than We Admit

At heart, the reproducibility debate is about values.

Science officially values:

- Accuracy

- Transparency

- Skepticism

- Shared knowledge

But in practice, it often rewards:

- Novelty

- Speed

- Prestige

- Positive results

Open science is not about mistrust. As its advocates put it:

Openness is not needed because scientists are untrustworthy - it is needed because scientists are human.

By changing incentives, science can better support the values it already claims to uphold.

Why Should Non-Scientists Care?

Reproducibility is not an abstract academic concern.

It affects:

- Which medical treatments are developed

- Which policies are justified by evidence

- Which findings enter textbooks and public discourse

When results cannot be trusted, society pays the price: financially, medically, and intellectually.

The reproducibility debate is therefore not a sign of science failing. It is a sign of science taking responsibility for its own foundations.

And that is something worth caring about.

The BioLogical Footnote

Perhaps the most uncomfortable implication of the reproducibility debate is that it forces us to admit that many scientific results were never meant to be durable. They were optimised for being publishable, not for being true. Seen this way, the debate raises a quiet but radical question: are scientific results events, or are they commitments? An event happens once and is remembered; a commitment must withstand being revisited, questioned, and tested by others. Reproducibility is therefore not just a technical standard or a methodological fix. It is a redefinition of what we expect scientific knowledge to be: less spectacular, slower to accumulate, but build to last.

To Explore Further

Reproducibility of Scientific Results | Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy