TL;DR

A gene is not a fixed thing with a single definition. It started as an abstract idea used to explain inheritance patterns, later became a stretch of DNA linked to proteins, and is now understood as a flexible, context-dependent set of genomic resources. Despite decades of new biology revealing layers of complexity (e.g. regulation, splicing, epigenetics, networks, etc), the gene persists because it adapts. Its power lies not in being precise, but in being useful: a concept that evolves with biology itself.

The Full Story

What Is a Gene? A Concept That Refuses to Stand Still

At first glance, a gene seems like one of biology’s most basic building blocks: a piece of DNA that makes a trait. Yet, for more than a century, scientists and philosophers have repeatedly questioned whether the gene is a clear, stable, or even useful concept. The surprise is not that the gene has been challenged, but that it has endured.

The reason lies in how scientific concepts actually work. They are not fixed definitions carved in stone. Instead, they evolve alongside scientific practices, technologies, and questions. The gene is a prime example of a “concept in flux”: its meaning has shifted many times, adapted to new discoveries, and diversified across fields, while remaining central to biology.

From Inherited Traits to Abstract Factors

The story begins with Gregor Mendel in the 19th century. Mendel did not set out to discover “genes” or laws of heredity. He was studying how traits behave in plant hybrids. His key innovation was methodological: focusing on individual traits, counting large numbers of offspring, and using a symbolic notation to track inheritance patterns.

From this, regularities emerged such as dominance, segregation, and independent assortment. Mendel spoke of “elements” or “factors” in reproductive cells, but he did not claim they were universal units of heredity, nor did he know what they were made of. The gene, at this stage, was not a thing but an inferred difference-maker.

Around 1900, Mendel’s work was rediscovered and transformed into Mendelism. These regularities were now treated as general laws of heredity, and the idea took hold that inheritance depended on discrete units passed through gametes. Still, these units were theoretical placeholders, not physical objects.

Naming the Gene, Without Explaining It

In 1909, Wilhelm Johannsen introduced the word “gene” precisely to avoid premature assumptions. A gene, he said, was simply “something” in the gametes that makes a difference to traits. He also introduced the crucial distinction between genotype (what is inherited) and phenotype (what develops through interaction with the environment).

This move was paradoxical but powerful. By stripping the gene of speculative meaning, Johannsen made it a workable scientific object. Genes could now be inferred from observable differences without committing to how they functioned or what they were made of.

Genes on Chromosomes, Not Blueprints

Early 20th-century genetics, especially through the work of Thomas Hunt Morgan and his group, linked genes to chromosomes. By studying fruit flies, they showed that genes are arranged linearly, can recombine, and can be mapped relative to one another.

This established the “classical gene” as a material unit located on chromosomes. However, even then, genes were not seen as simple instructions for traits. One gene could affect many traits, and many genes could affect one trait. Genetic causation was about differences, not direct construction. Development remained a complex, interactive process.

From Genes to Molecules

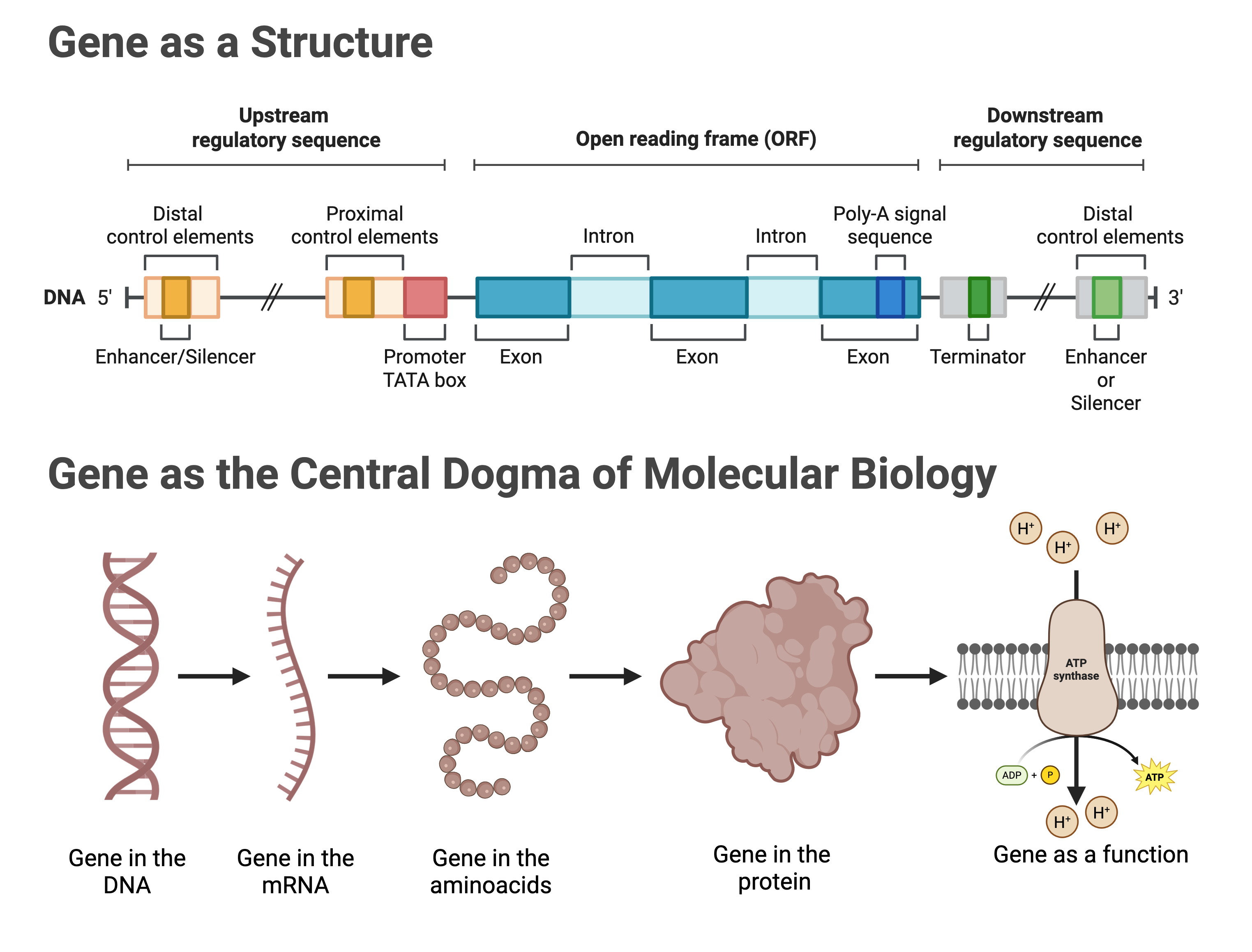

The mid-20th century brought a major shift: the identification of DNA as the genetic material and the discovery of its double-helix structure. This solved a long-standing puzzle: How genes could copy themselves, and reframed genes as sequences of DNA.

With the cracking of the genetic code, genes came to be understood as templates for proteins. This gave rise to the “classical molecular gene”: a stretch of DNA that is transcribed into RNA and translated into a protein. For a time, biology embraced a clean formula: one gene, one protein.

But this clarity did not last.

The Gene Becomes Complicated Again

Molecular biology soon revealed that genes are not neat, continuous units. In eukaryotes, genes are split into exons and introns; RNA can be spliced in multiple ways; editing, overlapping transcripts, regulatory regions, and non-coding RNAs are pervasive. One DNA region can produce many different products, and one product can draw on multiple genomic regions.

At the same time, gene regulation, development, and evolution revealed that DNA works within dense networks of interactions. Genes respond to cellular contexts; they do not act alone or issue fixed instructions.

Genomics and the Post-Genomic Gene

The sequencing of whole genomes intensified these challenges. Humans turned out to have far fewer protein-coding genes than expected, and much of the genome is transcribed without coding for proteins. Projects like ENCODE showed that functional genomic elements overlap extensively and defy simple boundaries.

This led to the idea of a “post-genomic gene”: not a single stretch of DNA, but a set of genomic sequences that together give rise to a coherent set of functional products. In this view, genes are defined as much by what they do as by where they are.

Many Gene Concepts, One Word

Today, biology uses multiple gene concepts side by side:

- Instrumental genes, used to predict inheritance patterns.

- Molecular genes, defined by DNA sequences and products.

- Developmental genes, understood as resources in complex processes.

- Post-genomic genes, seen as distributed and context-dependent.

None of these has replaced the others. Instead, the gene remains useful precisely because it is flexible. Its vagueness allows it to connect disciplines, adapt to new technologies, and support different explanatory goals.

Why the Gene Persists

The gene has survived not because it is simple, but because it is productive. It evolves with biology itself, absorbing new meanings without collapsing. Rather than being a fixed entity, the gene is a bridge between heredity, development, evolution, and molecular mechanisms.

The BioLogical Footnote

Asking “What is a gene?” has no final answer. The gene is not a settled object, but a living concept, reshaped whenever biology learns something new about life.